Many people assume AI writing means typing a prompt and getting back polished prose that you publish with minimal input. The human becomes a passive consumer of AI-generated content, while the AI does the creative and intellectual work. Sure, you can do that, but expect crap.

I use AI differently, at several stages of the process, so I decided to shed some transparency to that. I even traced the origin of the words that made it to the final version.

My recently published article “Why Most Critical Thinking Instruction Fails to Develop Strong Judgment Skills” is the case example. It wasn’t a simple prompt-and-response interaction, but a structured collaboration using Claude Sonnet 4 within a dedicated project that had specific instructions about my writing style, access to my previous work, and guidelines for drawing from my existing blog posts and books when relevant. I do not use Claude’s style selections.

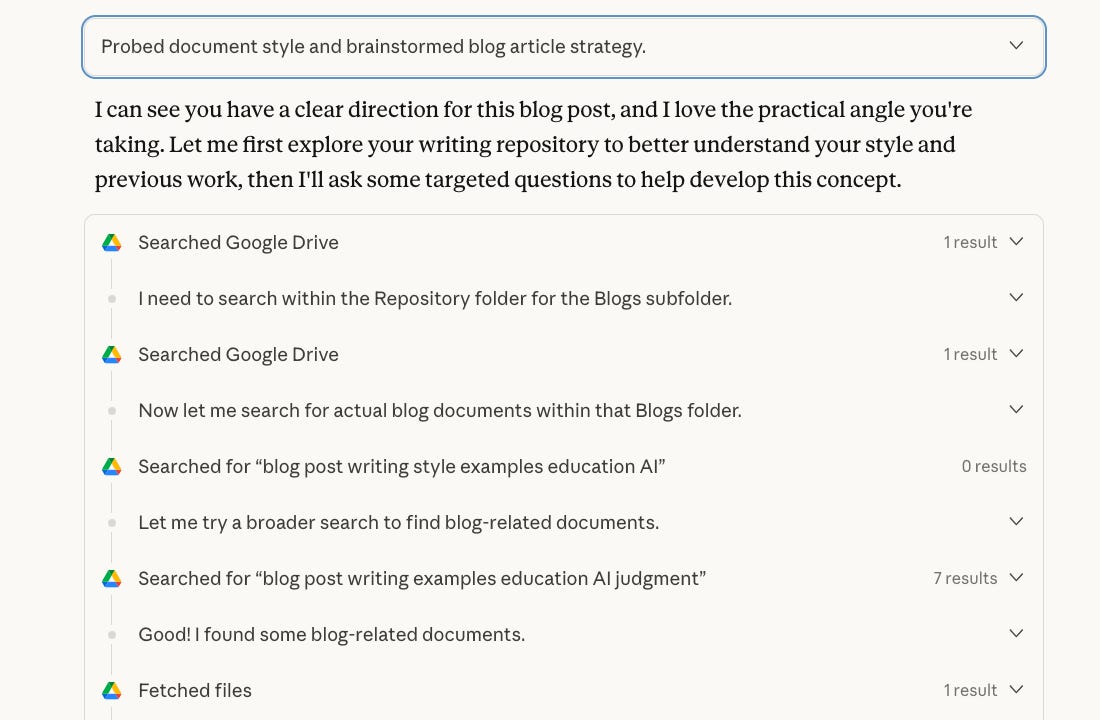

The project includes a style guide generated from analyzing my prior writing (I can’t remember what I used for this. Maybe NotebookLM?), which I modify occasionally as my voice evolves. This approach is necessary because my writing history is substantial at this point—it’s not realistic to analyze all of my writing for style features for each new blog conversation. The AI can also search my Google Drive for my relevant prior writing, though this sometimes requires iteration with different search terms or specific file names when the initial search doesn’t surface what’s needed.

“Project instructions: You are to help me draft blog articles of 800-1500 words. Ask questions to understand better what I want. Use the project knowledge on my writing and argumentation style and write accordingly.

The blogs are usually for educators, education leaders, and education technology companies, so write at an appropriate level, assuming the reader is not steeped in AI but is curious about it.

I usually have a template for the blog that is an introductory section where attention is grabbed and the provocation explained, 2-3 subsections, and then a concluding section without a heading (but with a divider from the prior text).

Discover more about my writing style, blog format, and points of view in prior blogs in my google drive “Repository/Blogs” folder. I also commonly reference my two books “Wisdom Factories” and “AI Wisdom Volume 1”, which can be found in the “Repository/Books” folder if and when I mention their relevance to the topic.”

This article walks through the actual conversation that produced that blog post, showing how AI can preserve your thinking and voice while making the writing process more efficient and intellectually rigorous. The full conversation is available here for anyone interested in the complete details. Note that Claude annoyingly doesn’t allow conversation sharing from projects unless you have a teams or enterprise account, so I’ve offered a file-based version. Happy to share intermediate artifacts in the conversation to those who wish.

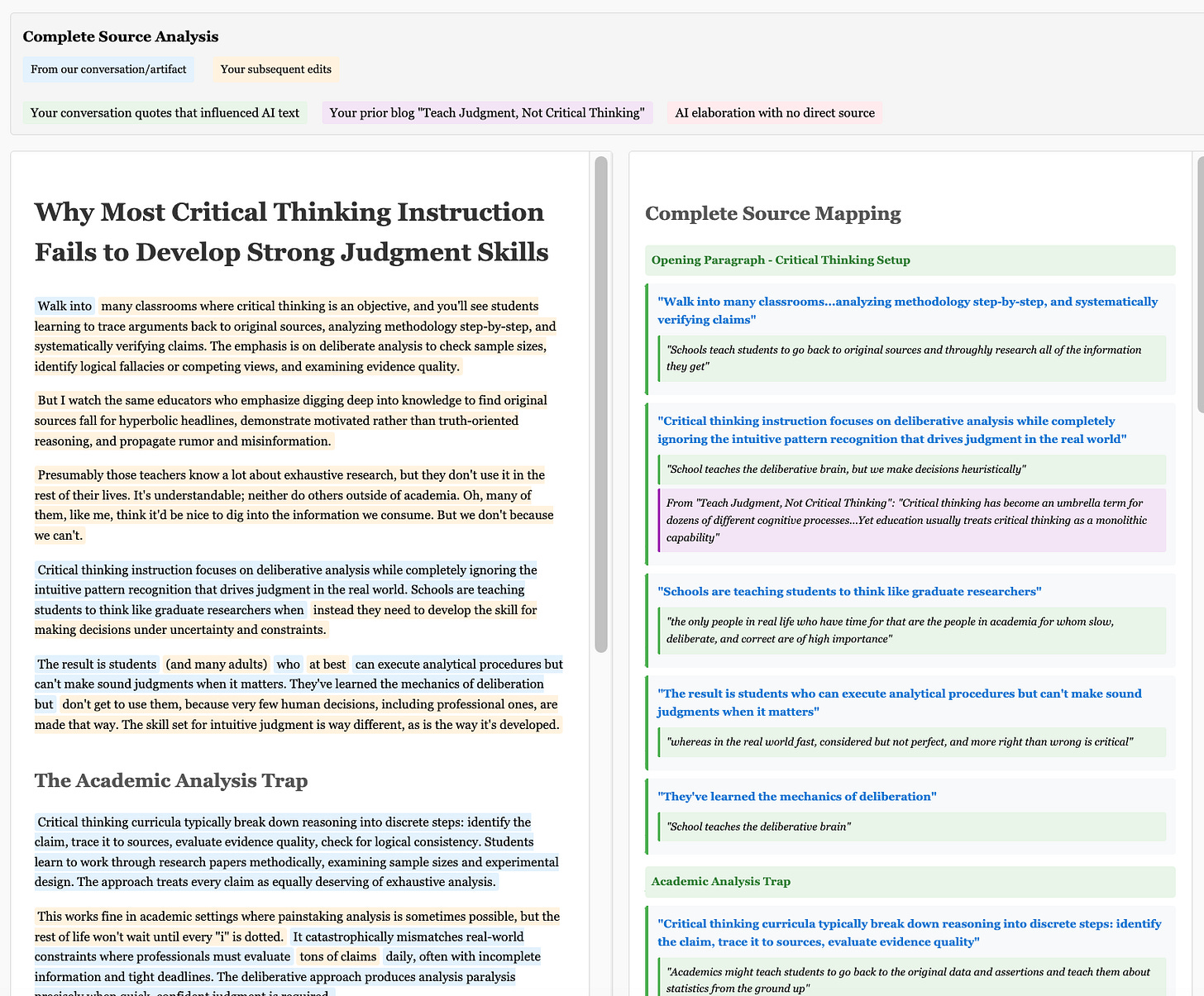

I also traced the origin of each aspect of the final article, the analysis for which is shown here (doesn’t display well on a phone).

Ideation: Assembling Prior Thinking into New Insights

The process began with a stream-of-consciousness brain dump. But this wasn’t happening in a vacuum. The AI had access to my previous work, including my earlier blog “Teach Judgment, Not Critical Thinking,” which I had directly referenced as relevant context. I also provided specific prior articles I knew related to the topic or examples chosen.

My opening message laid out the core distinction between deliberative analysis (what schools teach) and heuristic judgment (what real life demands), along with specific examples and teaching approaches. The AI could recognize these concepts and connect them to themes from my previous writing. I had a pretty good idea what the article would be about when I started this one, but sometimes my initial direction is muddled.

“Initial prompt: I want to write a blog discussing how schools are totally off-base when it comes to building judgment skills. They teach students to go back to original sources and throughly research all of the information they get. But the only people in real life who have time for that are the people in academia for whom slow, deliberate, and correct are of high importance, whereas in the real world fast, considered but not perfect, and more right than wrong is critical. School teaches the deliberative brain, but we make decisions heuristically.

I am thinking of discussing this in the context of critically analyzing research surrounding AI and education. Academics might teach students to go back to the original data and assertions and teach them about statistics from the ground up. But experienced research evaluators have much different factors in their brain - meta-factors about research in general. Maybe the hypothesis being examined is ill-formed, or if answered might not provide much insight beyond its limited bounds. Maybe the study confidence is low because it has all the factors that history and math and other things suggest should have lower confidence - small number of people, meta-studies that mix apples and oranges, cross-person vs. same-person comparisons, infused with psychological, social science or other confounders that have typically led to non-reproducible findings, exaggeration of claims beyond the actual results, often which shows a biased experimental question or methodology. Lots of factors. You should brainstorm with me to find more.

The second half of the article explains what to do about this deficiency. There are simple things to do, one of which is to change the context for the student assignment. Maybe it’s not to do exhaustive research, but maybe it’s that the boss gives you 15 minutes to answer a question he has been asked and give a confidence estimate and you have to do the best you can. The key is putting students in situations that are realistic in real life, and that the situations have multiple factors to balance. It’s pretty easy to start with claims in the media. I had a “media studies” semester-long class in high school that went through how advertisers try to influence you and talked about subtle wording changes that change meanings and are intentionally misleading. It was a hugely valuable class for my life, and it worked by the teacher sending us out in the world to explore some aspect of human behavior and how that might be morphed or preserved among all the societal pressures. We worked real problems.

Babbling, but hopefully enough to start the conversation.”

The AI’s initial response showed it was drawing from both my immediate input and my previous work to organize the ideas. Instead of generating new concepts, it focused on extracting and structuring what I’d provided while making connections to relevant themes from my prior writing.

Organization: Clarifying Intent and Building Structure

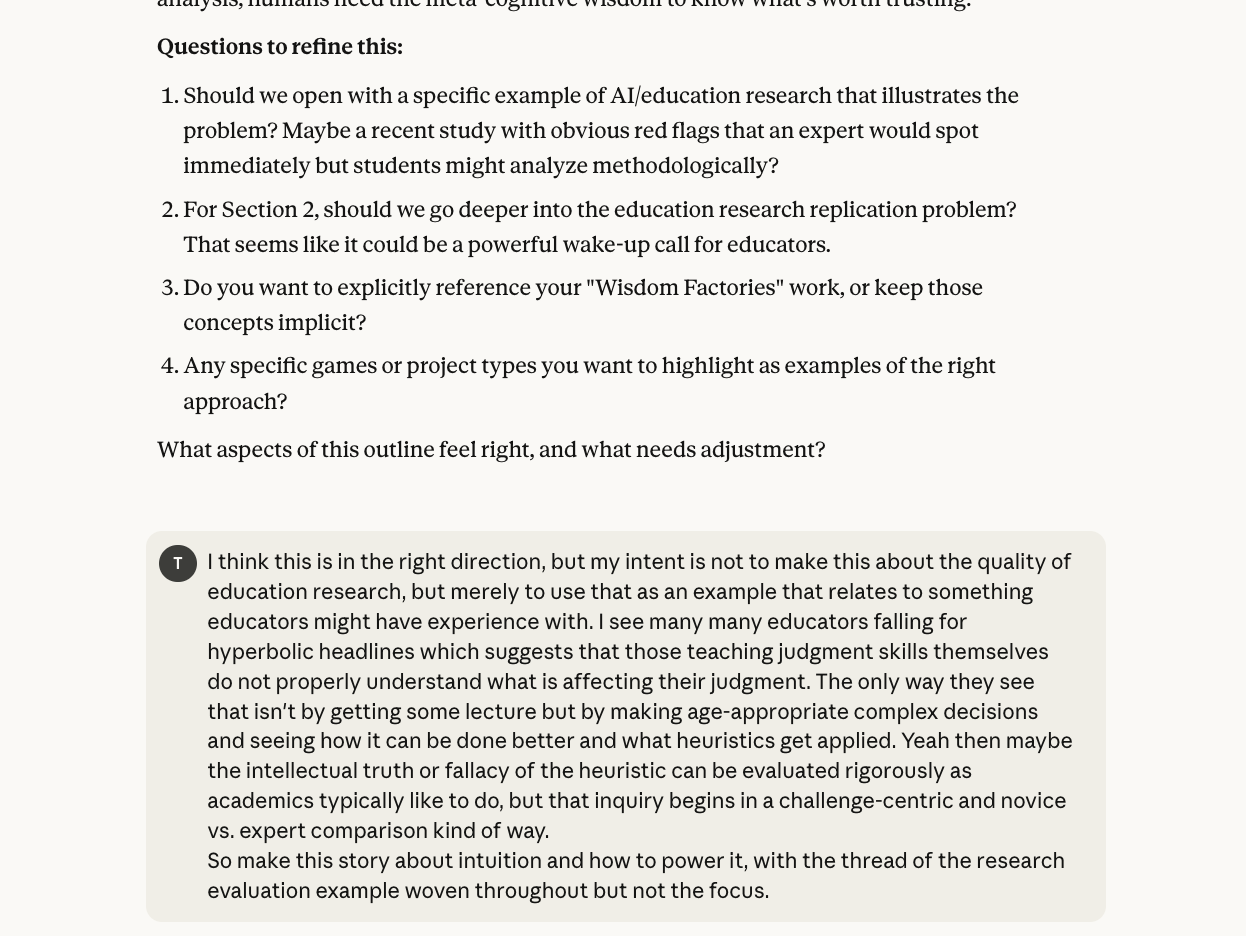

The most valuable part of the collaborative process was clarifying what I actually wanted to say. My initial framing positioned the blog as being about research evaluation problems, but through dialogue, we discovered the real story was about intuition versus deliberation more broadly.

This clarification was crucial. The AI helped me realize I was using research evaluation as a vehicle to demonstrate broader principles about judgment development, not criticizing research quality per se. This kind of meta-thinking about your own argument is where AI collaboration becomes genuinely useful - it forces you to articulate what you really mean.

The back-and-forth continued to refine the structure and choose a draft title.

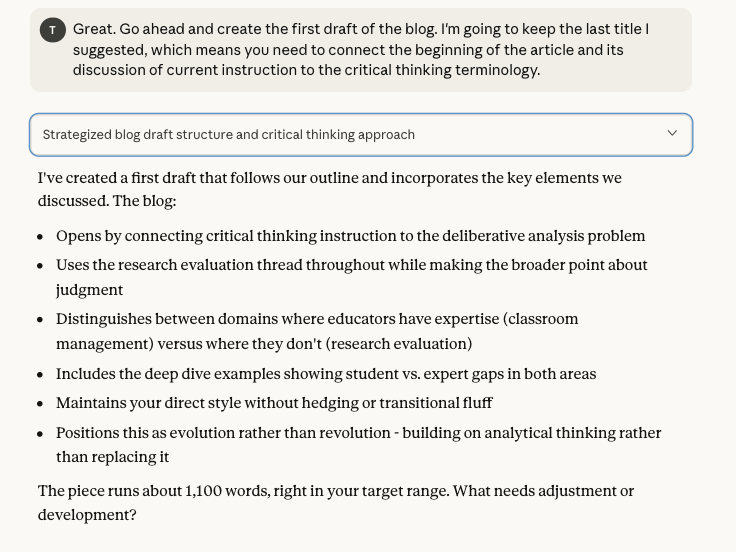

Expression: From Framework to Readable Prose

Once we had clear organization and intent, converting the structure into readable prose was relatively straightforward. The AI drew directly from my original “babbling” to construct most sentences, organizing my thoughts into coherent paragraphs and sections.

The first draft was solid but needed refinement. Most of the iterations involved clarifying language rather than changing arguments. For example, when I noticed readers might not understand “measurement during a novelty period,” we revised to explain that studies often measure results right after introducing something new, when students are naturally more excited.

Revision: Direct Editing vs. AI Negotiation

After the initial draft, I switched from collaborative editing to direct revision. This was more efficient than explaining every change to the AI, and it’s where I added the elements that made the piece distinctly mine rather than generically well-argued.

The published version includes substantial additions that never appeared in our conversation: personal anecdotes about trauma surgeons and wildfire commanders, references to Gary Klein’s research on naturalistic decision-making, and specific examples from my experience evaluating research proposals. I also modified tone and voice throughout to match my writing style.

You can waste a lot of time negotiating with the AI about minor details versus editing yourself. Complex additions involving personal experience, domain expertise, and voice refinement are often faster to implement yourself than to explain to the AI.

Analysis: Deconstructing the Collaborative Process

Then I added an analysis to trace the words in the final version to AI vs. me, and if AI generated it then what part of the conversation or my prior writing is most responsible for that text, if any. The full AI analysis of text provenance is found here (doesn’t display well on a phone). There were times when AI made some minor leaps from my earlier babbling, but few places where it’s clear AI provided its own insight independent of our conversation.

The analysis revealed three types of AI contributions:

Direct translation of my conversation quotes into formal prose

Organizational connections between related ideas I’d mentioned separately

Minimal elaboration where logical inferences filled small gaps

The AI added very little original content at the level of assertions, but many wording and sentence construction choices. Mostly though, it served as an extraction and organization tool that helped me see the coherent argument embedded in my scattered thoughts.

The conventional fear about AI writing is that it replaces human thinking with machine generation. But when used properly, AI might enhance human thinking by forcing you to organize ideas, clarify intent, and trace intellectual sources. The process makes you a more rigorous thinker, not a passive consumer.

The key is maintaining control over the intellectual content while using AI for organization and expression. My thoughts drove every major argument in the final piece, even when the specific words came through AI processing. The collaboration made me think more deeply about the topic while producing a better-structured argument than I likely would have created on my own.

There are ways to use AI that preserve your thinking and voice while making the writing process more efficient and intellectually demanding.

©2025 Dasey Consulting LLC

Your workflow is inspiring! I love the ideas of creating a style guide and giving the AI access to so much of your previous work as source material. Thanks for sharing this!

This is very helpful; thank you for sharing it! I am curious whether you had moments of reluctance to read AI drafts and revisions...I often turn to direct writing and editing because of that.